Poland, my adopted home since four months, is a country of many associations, albeit often based on cliches. Your associations may be negative: you could think of the troubled history and ongoing struggle to find its place in Europe. They might be positive: a dynamic economy of hard working people valuing family and tradition.

Either way, Poland may not strike you as an extremely happy place. And you are right: Polish hovers somewhere around one-third in the World Happiness Report, ranking 46th out of 155 in the 2017 edition.

The Polish way of happiness

But how happy are Poles really? Is there a Polish way for happiness? These are some of the questions I wanted to research as I moved here.

In my search, I encountered a recent book written on the topic: “Somehow it will be: the Polish way of happiness”, or “Jakoś to będzie. Szczęście po Polsku”. I set out to meet one of the four authors, journalist Beata Chomątowska, to ask what this concept of ‘Jakoś to będzie’ means.

The book, which she co-wrote with Dorota Gruszka, Daniel Lis, and Urszula Pieczek, was born when they noticed a flurry of books on hygge had hit Polish book stores. “Why are Poles reading about hygge? Denmark is doing such a good job in advertising its country. We thought we could also show Poland and Jakoś to będzie as a source of happiness,” Chomątowska said.

The book thus inspires Poles (and foreigners) to take the old-Polish life philosophy to heart, rather than trying to be calm and light candles. The word ‘hyggeligt’ does not come in mind when thinking about Poland.

Jakoś to będzie

As Chomątowska told me, Jakoś to będzie means something like ‘we will make it’, or ‘somehow it will be’. “It is the most appropriate title. Poles got used to deal with very hard circumstances, to be miserable. Regardless how bad it is, we will manage.”

(After being partitioned between Austria, Prussia and Russia, Poland disappeared from the map in 1795 and only returned in 1919. Twenty years later, World War II and then Communism followed. Poland again became a democracy in 1989).

The book then describes the ‘creative tensions’, or paradoxes, that Chomątowska and her co-authors see in their nation. They are hospitable to their guests, but quarrelsome among themselves. They are ingenuous, but desperate. They are working hard, but also enjoy festivities. All these elements make Poles Poles, and describe their approach to happiness.

Without danger, Poland does not thrive

According to Chomątowska, the Polish way of daily life is not made for happiness. She sees Poland as a ‘anti-hygge’ society that cannot live in stability. “Ordinary life is too boring. We can’t deal with it. We need the rush of adrenaline and can’t stand stability for a long time. We always had to fight and be active to reach our goals, like independence”. Without danger, Poland does not thrive.

That doesn’t bode well for happiness. But the picture is changing. Happiness levels tremendously increased in Poland, as the country is one of the biggest economic success stories of the last 25 years. The population enjoys higher salaries and higher wellbeing levels than before. While the country orients itself to Western Europe, Poland is now one of the happiest countries of Central and Eastern Europe, as Poles are often surprised to hear.

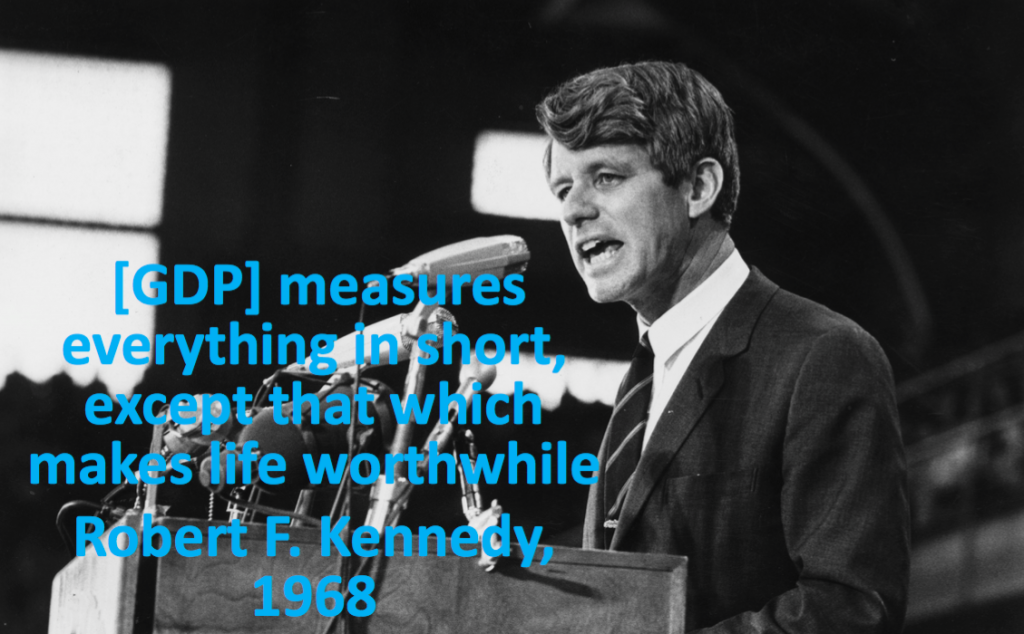

And there are more hopeful signs: a public debate on how a life should be well lived is slowly emerging. After the fall of capitalism, capitalism ran wild during the 1990s, but attitudes have been shifting since. “For twenty years, GDP was a fetish. But the younger generation is more aware that there is no sense in working 12 hours a day and run like a hamster in a wheel”.

Finding happiness in unhappiness

Whatever the future holds, Poles have an amazing skill, says Chomątowska:

“Poland is a land of paradoxes. We find happiness in unhappiness. We find it in actions to change our circumstances because we don’t feel good. We have the ability to create something from nothing”.

And thus, jakoś to będzie. Somehow, it will be.