Guano – basically bird dung with an exceptionally high quality as fertiliser – was a highly demanded product. Mainly found on Pacific islands off the coast of Peru it was a popular agricultural fertiliser since the 1840s. From the 1850s, demand sky-rocketed, and competition for guano deposits was fierce. It was guano that was at the basis of the United States imperialist tendencies. The Guano Island act of 1856 allowed US citizens to take control of unclaimed islands.

Why is this relevant, and what does it have to do with GDP?

Guano soon made the people mining it rich. But the environment suffered: it took few decades to exhaust all reservers and leave the islands containing deposits bare. Favouring short-term economic gain over long-term environmental sustainability destroyed the islands.

Guano is just one example, but fits a long human tradition of discovering, using, and then exhausting precious resources, without batting an eye about the environmental consequences – very often driven by the desire to achieve economic growth and increase GDP. But compared to the 1850s, we have a lot better understanding of how these patterns go, and a larger awareness that alternative strategies are possible.

The World Before and During GDP

The World After GDP, a new book by Lorenzo Fioramonti, offers some of thoughts to escape this trap. It starts by the notion that today, with the exceptions of few isolated and traditional populations, human beings above all are consumers. Private consumption is what is at the basis of GDP and keeps economies going.

GDP however has a bit different origin: it started as a tool to help the English king and French sovereigns in the 17th and 18th century determine how much tax their populations could sustain. The modern institution of GDP developed as of the 1930s, when economic Simon Kuznets helped the US administration understand the national income. Over time, GDP evolved from a metric to see the size of the economy to a goal per se.

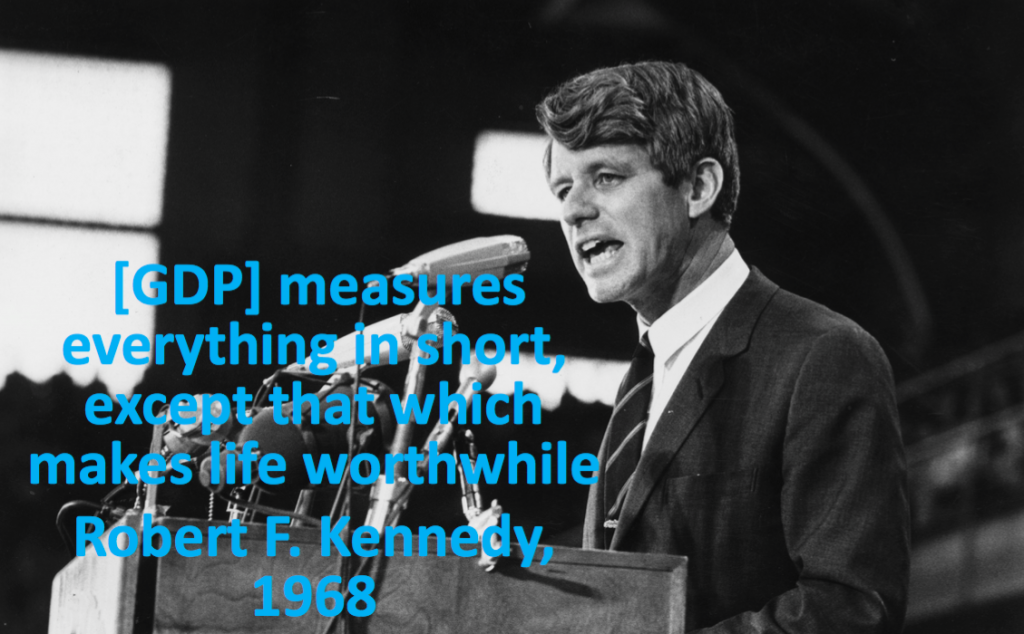

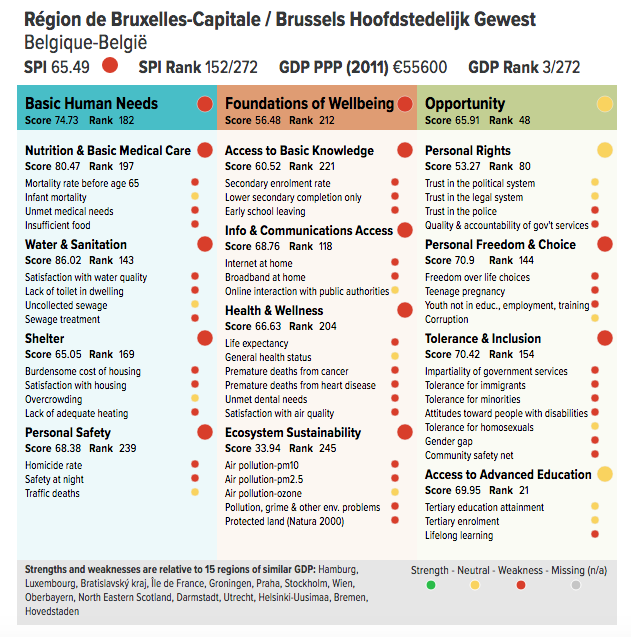

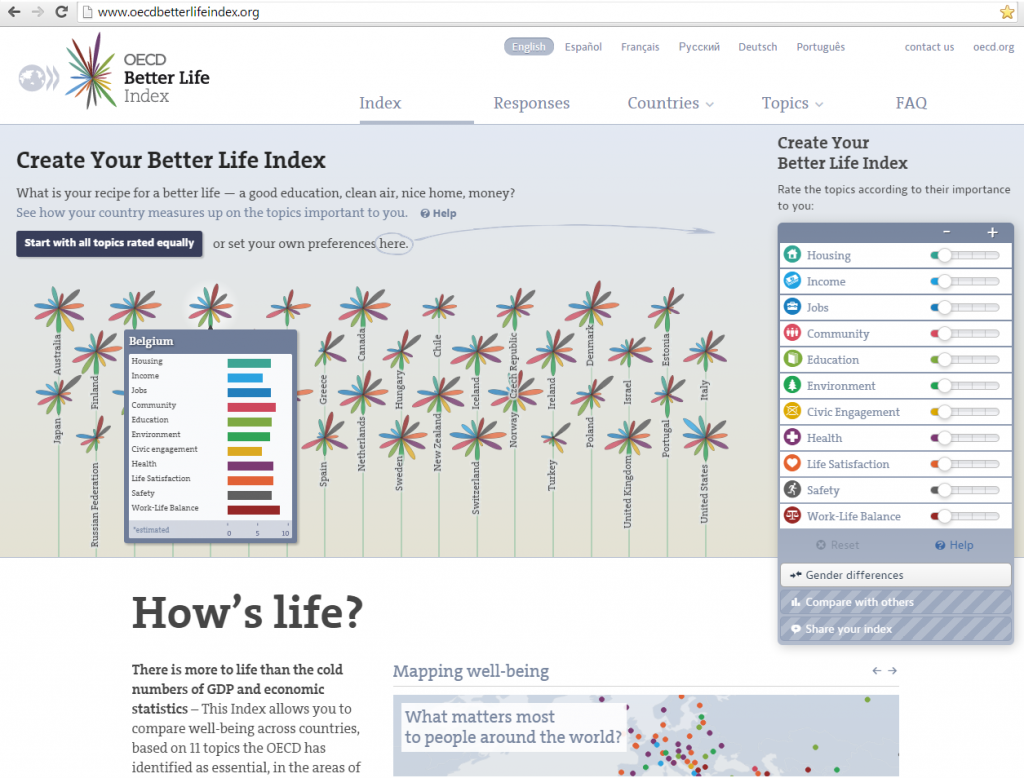

Revise GDP, but don’t dethrone in favour of another flawed indicator

The beyond GDP argument that Fioramonti also makes has already been widely discussed on this blog. Fioramonti discusses, and welcomes, the many contenders of GDP. He dedicates some attention to the Human Development Index, the OECD’s Better Life Index, Gross National Happiness, the Social Progress Index, and more. He also notes that the criticism has resulted to some top-down changes to GDP, such as statistical revisions to add up the black market to national economy. The change to consider investment in research as a benefit rather than a cost is another example.

The Nordic leaders (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Iceland) poking fun at US President Trump and Saudi king Salman. What if they would lead the G7?

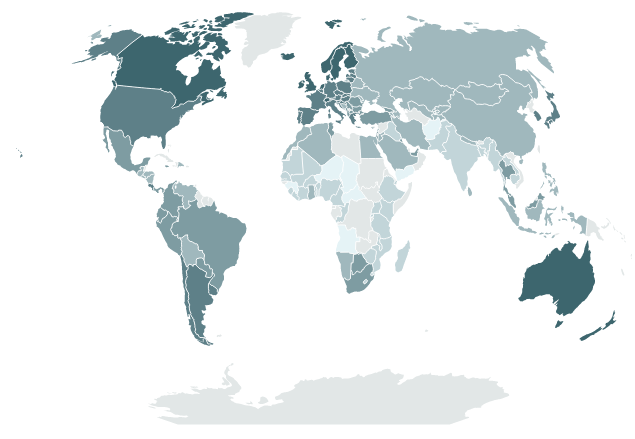

Ultimately, Fioramonti very sensibly states that all those alternative indicators, like GDP itself, only display one approach to wellbeing. Therefore he speaks out against replacing GDP by another, again inherently subjective and likely flawed, indicator. At the same time, these sections are full of careful reflection on the beyond GDP revolution, and contain interesting ideas. For instance, his mapping of alternative G7 is provided an interesting narrative. The strongest 7 countries of sustainable development does not contain any of the largest economies, but brings Costa Rica, Colombia, Panama, Ireland, South Korea, Chile and New Zealand together. The G7 of happiest countries includes Denmark, Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, Finland, Canada and the Netherlands. A G7 lead by these countries would be, well, a lot of different.

A bottom-down revolution?

Apart from the top-down changes, Fioramonti also sees a bottom-up pressure on GDP. This is where his book stretches beyond the usual beyond GDP literature. While he has a point that there is an increasing community of ‘de-growth’, authentic consumption, local produce and peer-to-peer services, the question is how much we really should read into this. Does someone who drinks a regional craft beer really has his lower contribution to GDP in mind when he sips away, or does he simply value the idea of getting something from close by?

And, isn’t there a lot in the ‘sharing economy’ that has little to do with sharing? AirBnB and Uber, referred to at multiple occasions by Fioramonti, do not only have positive effects. For instance, in reducing the cost of a car ride in New York, Uber drives people out of the metro and into congested traffic. AirBnB makes it easier for people to travel, but creates it own ‘buy to rent on AirBnB’ market, pushing residents out of inner cities and seeing them replaced by one-time consumers. Modern technologies thus simply are used to generate returns in a more modern way. While the book is well thought through and a worthy read, it may stretch the argument a bit to call this a post-GDP world.