What does happiness look like in Turkey?

That’s the main question I dived in during a few days in Istanbul two weeks ago, as I spoke at a conference on Determining the Happiness Map.

At the conference, hosted by Tüses and Kadıköy municipality, I spoke alongside professor Erhan Dogan (Marmara University Istanbul), Ragnhild Bang Nes (Norwegian Public Health Institute and Oslo University), and Jochen Dallmer (University of Kassel).

Happiness in Turkey

It’s a funny idea to have researchers from cold Northern countries like Norway, Germany and Netherlands come to Turkey to speak about happiness. Many of our chats on happiness focused on the relevance of good weather, tasty food and the street life culture for happiness. While all of those are present in Mediterranean Istanbul, they’re not factors that North-West Europe is known for.

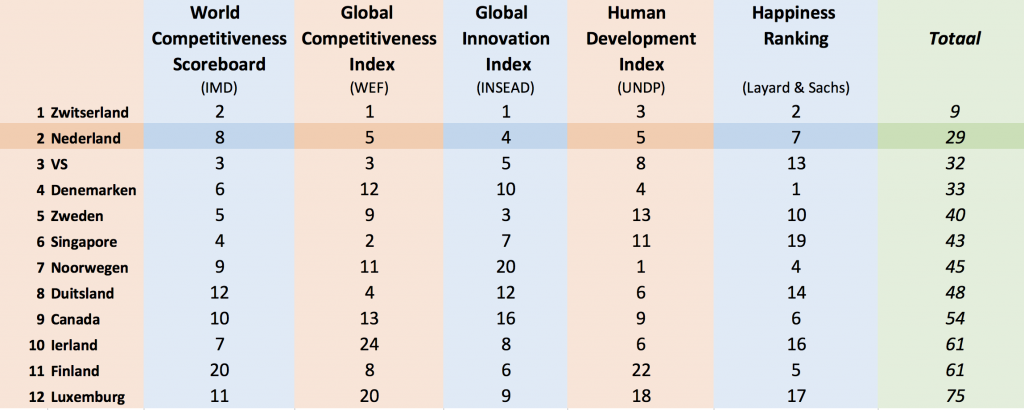

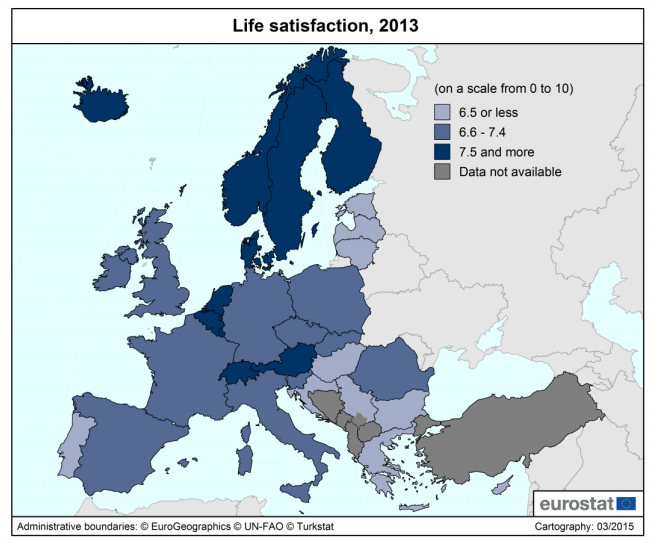

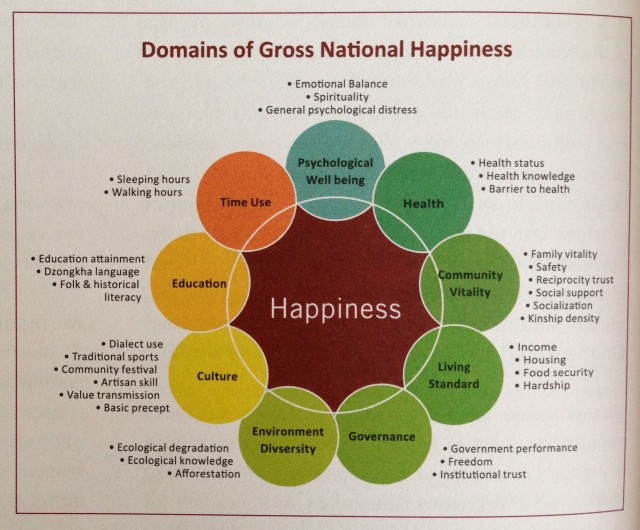

That factor highlighted one of the interesting elements we came to discuss: happiness and quality of life are not the same. While Turkey may have a warmer temperature and a Mediterranean cuisine on offer, some of the key features that contribute to quality of life are less prominent. Norwegians may or may not enjoy themselves more than Turks, but perform well on loads of factors that matter: high incomes, a strong collective social support mechanism, and personal freedom.

How much work do we need to do in life?

A few takeaways from the conference:

- Turkey’s level has increased over the years. In the 2017 World Happiness Report, Turkey scored about 0.3 points higher (for 2014-2016, compared to 2005-2007). According to prof. Dogan, the factors of GDP and social support are most prominent in explaining the level of quality of life. In that matter, Turkey is quite similar to many other countries. To the contrary, only a relatively small part of the happiness level is explained by generosity. Correlation of course does not equal causation, and there is no direct causal relation, but nonetheless there might be a case to promote generosity!

- In Norway, the qualify of life is high, resulting in a 1st spot in the World Happiness Report for 2017 (though it was overtaken by Finland in the 2018 edition). But that doesn’t mean all is well. According to Bang Nes, suicide rates in Norway stand at around 11 per 100,000, almost triple the 4 per 100,000 in Turkey. At the Public Health Institute where she works, efforts are made to better understand how people live longer and healthier lives. Better data on happiness and mental health are collected, in order to guide public policy.

- My third fellow speaker, Jochen Dallmer, looked at the German public debate on quality of life, and especially the role of sustainability. His PhD research is about a complicated question. We know that we should change our lifestyles to get back in the boundaries of the single planet we have. Happiness now is often associated with hedonic pleasures. Could an ascetic lifestyle provide happiness? He also posed another very un-German question: how much work do we need to do in life? And finally, he spoke about the German quality of life data collection, which he felt mainly conveyed high quality/standards.

My own 20 minutes of fame: happiness in the Netherlands and Poland

- Finally, my own 20 minutes of fame were dedicated to the development of happiness levels in Poland and the Netherlands over the last 25 years. Dutch happiness level stayed broadly stable, and slowly a more active public debate on well-being policies is emerging. Until the elections of this month, the municipality of Schagen had a Councillor for Happiness (with Finance as his primary portfolio). And similar to the Norwegian and German efforts, a new Broad Wellbeing Monitor mapping happiness is being shaped after a hesitant start.

- Poland has seen massive transformations since the 1990s, and also the domain of happiness has not been left untouched. Even with social ineqaulity rising, happiness levels icnreased, likely in connection with tremendous economic growth. But also Poland shows awareness that there’s more than work and GDP. The Pracuję bo lubię (‘I work because I like it) project is one example taking happiness as inspiration.

And my own happiest moment in Turkey? A lost Sunday afternoon hour in company of old and new friends, spent basking in the sunlight with a view on the sea of Marmara.