Quiz question: which country is happier, the United States or Mexico? Based on what you read about wealth, migration and violence, you’d probably guess that the US outranks Mexico. This is not the case. In the World Happiness Report, Mexico scores a 7.088, just above 7.082 for the US. In other polls, Mexicans often score around 8 out of 10. What explains their happiness level?

The last two weeks I wrote about my main takeaways from the Well-being and Development Forum in Guadalajara that I attended, and about my own presentation. Today, I want to face a question that was the biggest one of the conference (and the title of one of the final panels): why are Mexicans so happy?

Data presented by some of the researchers illustrated that happiness in Mexico is surprisingly high: around eight points on a scale of ten. As everywhere, different factors contribute to (un)happiness. Professor Rene Millan Mon had measured performance on six factors to explain happiness. Of these, having the freedom to make own choices, a person’s health, and family relations, explained the largest part of happiness levels. Other factors – habitat, education and government – have a lower impact.

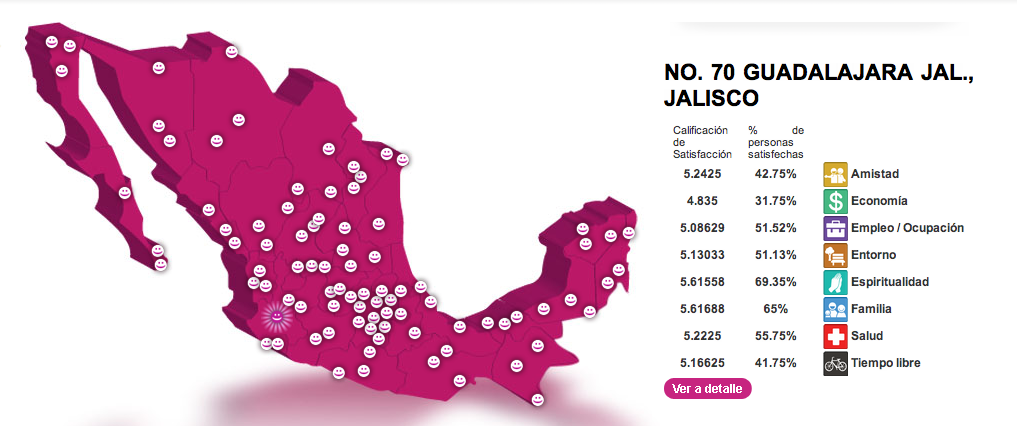

What was also remarkable to see is that Guadalajara, Mexico’s second city and the place of the conference, scored comparatively low. In a study of Imagina Mexico, it ranks as 70th out of 100 cities. It has good scores for spirituality and family, but a lot lower ones for economy, free time and friendship. And within the state of Jalisco, all more rural regions have higher happiness levels than this city of five million.

Why is that? In the end, it shows we don’t have the full answer about Mexico’s happiness. The World Happiness Report distinguishes six elements that are thought to be determinative for happiness. These six – economic, health, social support, personal freedom, generosity, and perception of corruption – only explain about four points out of the 7.088. If we assume that measurements of happiness are scientifically sound and that the number really grasps how Mexicans feel, we simply don’t know what makes Mexicans so happy.

But this outperformance is not only visible in Mexico, but also in other countries in Latin America. I use to refer to it as the ‘Latin American happiness bonus’. Apparently there is something in Latin American culture that makes them happier than you would expect based on objective factors.

When asked, Mexicans themselves seem to think that strong social ties are one of the factor. Indeed, many people live a very active public life. The streets are full with people, and family ties are tight. But the question is whether this has emerged out of his own, or as an alternative structure to counter the negative effects of low public trust and a low quality of social security. The ‘fiesta’ culture could be another explanation. For instance, the quinceneria parties are a reason for a huge party, but also mark a key step or ‘accomplishment’ in life.

But social support is one of the factors studied in the report, and one that has the strongest relation with happiness as far as the data indicate! It might be that we still undervalue its significance in the data, but in the end, we don’t have the full answer. I experienced Mexico as a country full of contrasts. When reading about Mexico, I mainly read about violence, migration and drugs. Whilst social inequality, and protests about disappeared students were not far away, as a tourist I mainly experienced the warmth of the people, the beauty of their country, and also some pride about their enjoyable things (and about high happiness levels, too!). Maybe the surprisingly high happiness levels is just another contrast.