Something is special in the state of Denmark. Believe it or not, but despite associations with the grey weather, not-so-outgoing personalities, and general boredom, Denmark tops the ranking in many international happiness surveys. Denmark is the happiest country according the World Happiness Reports of 2012 and 2013, the European Social Survey of 2008, and the Eurobarometer of 2012.

What is so special about Denmark? Why are Danes so damn happy?

The Happiness Research Institute, or Institut for Lykkeforskning as it sounds in Danish, was founded a couple of years ago just to answer that question. And the answer is simply that Denmark is good in almost everything that is related to happiness. In the words of John Helliwell (Author of the World Happiness Report, and winner of the Nobel Prize for Happiness, if there had been one):

Broadly speaking, Denmark ranks highly in all factors that support happiness

The factors behind Danes’ high happiness

What is behind this happiness? According to the Happiness Research Institute’s study on The Happy Danes, there are eight factors that contribute to Danes’ high happiness levels:

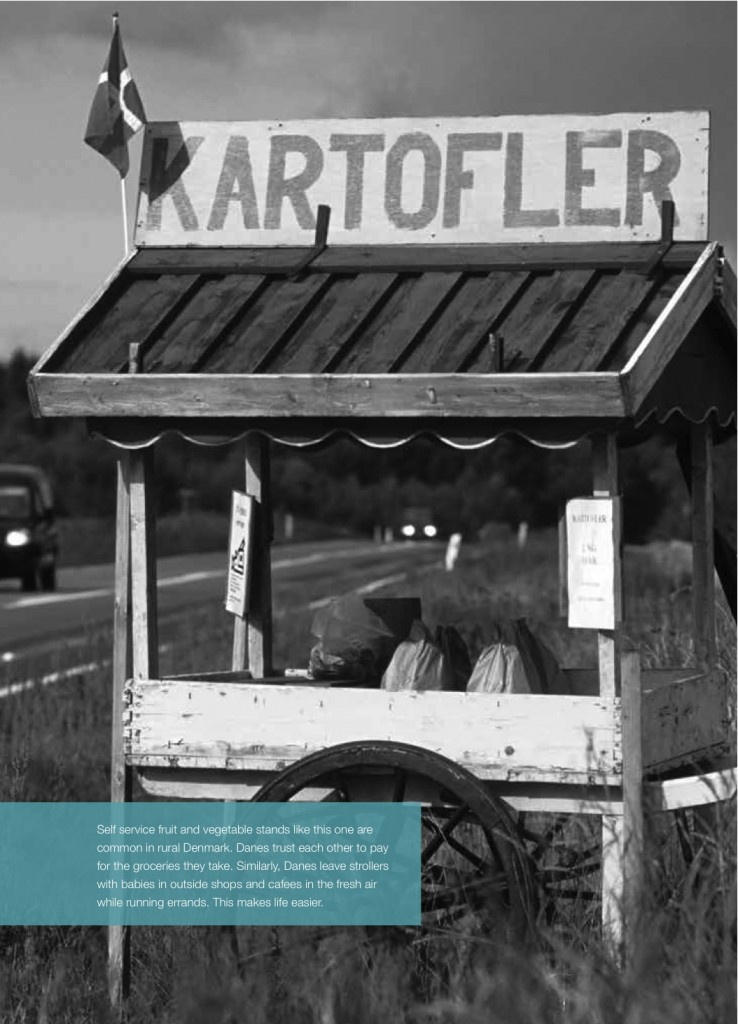

- Trust. People tend to trust each other – this even comes in crazy forms: I’ve been told that in Denmark it’s completely normal to leave your baby stroller (baby included) outside the supermarket during groceries or at a bar when you get a coffee.

- Security. The welfare state helps. Even if you’re poor, or unemployed for a time, the state takes care of you. Comparatively, Danish poor have a high level of well-being.

- Wealth. High prosperity helps!

- Freedom. And personal freedom, too.

- Work. And on top of that, a healthy relationship to work! High levels of autonomy and job quality – that makes happiness at work?

- Democracy. Election turnout of over 80% – and voting is not mandatory!

- Civil society. Beyond a high degree of voluntary jobs, Danes also socialise more than average.

- Balance. A balance between work and leisure.

All in isolation, none of these factors are very special. There are countries that offer social security, that have a strong democratic culture, or where people have a good work-leisure balance. The special thing about Denmark, though, is that all these factor appear together. What is the secret?

Social security, but no happiness policy

I asked Meik Wiking, the Director of the Institute and the lead editor of The Happy Danes, whether there is an overall policy framework dedicated to the pursuit of happiness in Denmark, or whether it is just the consequence of high quality policies in the individual areas mentioned. Wiking answers:

Currently, there is no overall happiness framework (…) However, I do think that the Danish welfare state has been good at having citizen-centered policies and focusing on reducing UN-happiness: ensuring basic income, access to health care, education etc.

As the report explains, social security has contributed to the fact that the gap in happiness between rich and poor in Denmark is a lot smaller then, for instance, in the US.

Trust

Trust is the first factor that the Institute identified as contributing to happiness. That begs the question why trust is so high. Wiking points at the low level of corruption and the small size of Danish society:

One element is of course the low level of corruption. We experience that we can have trust in our system and in our society. We are treated equally and fairly according to the law. Also, I believe that the equality and the smallness of our society reduces the incentive for cheating. We all have more or less the same – and in a small society (where everybody knows each other) the penalty for cheating is higher. I know this is all very banal, but it is the best explanation I can see.

The positive emotions paradox

Danes don’t have a reputation for being the most cheerful people. And indeed, they score lower on ‘positive affect’ (or short term, intense, positive emotions) then for instance some Mediterranean or Latin American countries. But the scores are higher for overall quality of life, where happiness measurements are based on longer term and more evaluative judgements about life as a whole. Isn’t this paradoxical?

I do believe we should strive for having high levels on both the evaluative and the affective dimension in every country. Life is made up of moments and the two dimensions are linked. However, I am not sure we should call it a paradox that one country scores low in one and high in another. I think it is just evidence that we need a more nuanced language – and understanding – to be able to talk about, study and improve quality of life.

Thus, Danes are a happy people, even though positive emotions are lower than in some other countries. In the end, it simply means that there is a lot more to know about happiness. Even in Denmark, the Happiness Research Institute won’t be out of work.