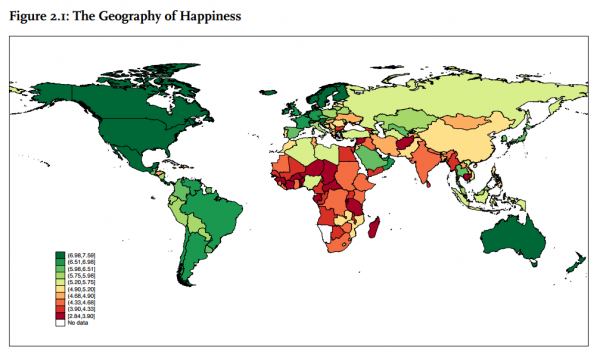

The World Happiness Report 2015 is out and struck some headlines last week. Number one this year is Switzerland, and Togo comes last. But beyond praising winners and shaming losers, there is a lot more of interested figures to find. A quick selection of some of them.

The good news: how happy are we?

- Let’s start with the good news. Of 130 countries where it was possible to compare data from 2012-2014 with 2005-2007, 53 saw significant improvements in happiness levels (41 decreased and 36 had no meaningful change). This suggests the world is a slightly happier place then it used to be.

- The biggest improvements were made in Nicaragua, Zimbabwe, Ecuador, Moldova and Sierra Leone, who each added around one full point in their score.

- It’s the well-expected developing countries that fill the top-1o: Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Canada, Finland, Netherlands, Sweden, New Zealand, and Australia, all a solid 7.3 or higher

- … and what’s the score of the number one, Switzerland? With three decimals to be Swiss and precise, we get to 7.587.

Other good news (but not in stats)!

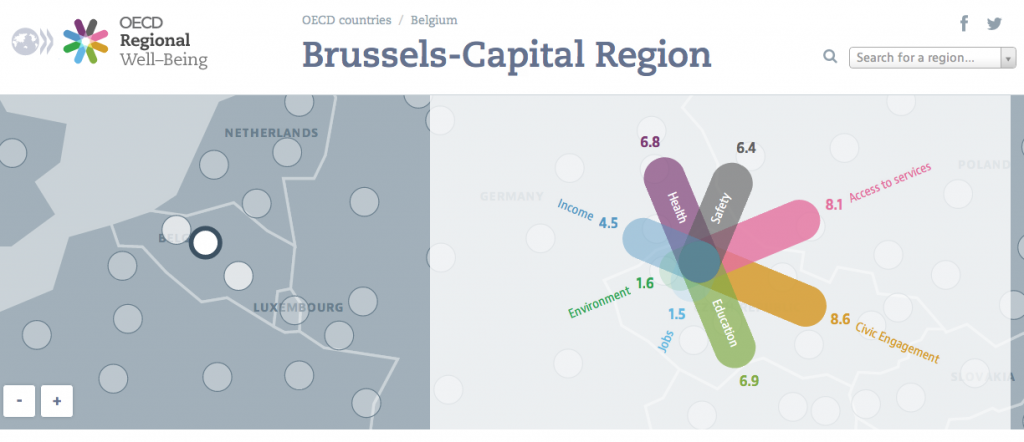

- The most important sections maybe are not those listing the countries, but providing case studies of cities and regions who have changed their policies to make use of all the knowledge about happiness, from Dubai to Jalisco (Mexico), and from Santa Monica to Bristol.

- At the same time, progress is also made in the neuroscience of happiness. A dedicated chapter 5 summarizes some of the findings. For instance, evidence about the link between positive emotions and happiness appears to be stronger and stronger.

- There is more and more understanding about the various distribution patterns of happiness within age groups and genders. Overall, women are slightly happier than men. Over age groups, the patterns differ per region: in Central and Eastern Europe, Central Asia and South Asia, happiness goes down as age progresses. But in East Asia, but also in Western Europe, the best comes last: happiness levels go up as people enter their 70s.

The bad news: how unhappy are we?

- There is still a lot, a lot of misery on our planet. More than fifty countries have happiness levels below 5.

- And the worst-performing are truly miserable. Countries like Syria and Afghanistan, but also Rwanda, Benin and Burundi fall under 3.6 The lowest level is found in Togo at 2.839.

- Two countries on different sides of the Mediterranean – Egypt and Greece – have lost more than one point. And some others (Jordan, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, and Italy) lost around three quarters of a point.

- For instance, the case of Italy (-.764, now at 5.948) is worrying. Usually, a high happiness level means a high level of resilience in phase of challenge. This fabric might be unraveled as result of the crisis Italy is going through.

- To end with a positive note: he best ‘losers’, as far as one could be a loser with a score of 7.527, are the Danes. Denmark typically ranks one in most of the happiness report. I have been told that usually, it is no news when a happiness ranking is published, but this time it was: apparently, Danes are not used anymore to come second (or third, as now).

And now?

The 2015 World Happiness Report comes out with a large ambition: influencing the next development goals. As the UN prepares to adopt Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to succeed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) this year, the hope is that happiness outcomes are targeted within the SDGs. A worthwhile ambition: ultimately increasing human happiness and its fair distribution should be the goal of public policy.

One concern: the SDG process appears to be very complex, with over 150 different – and often, vague – ideas currently on the list of goals that could be adopted later this year. In such a process, they risk to lose their meaning. But either way, the wealth of statistics provides a lot of inspiration and background data to policy makers to make the world a happier place.